Week Seven: October 6 - 12

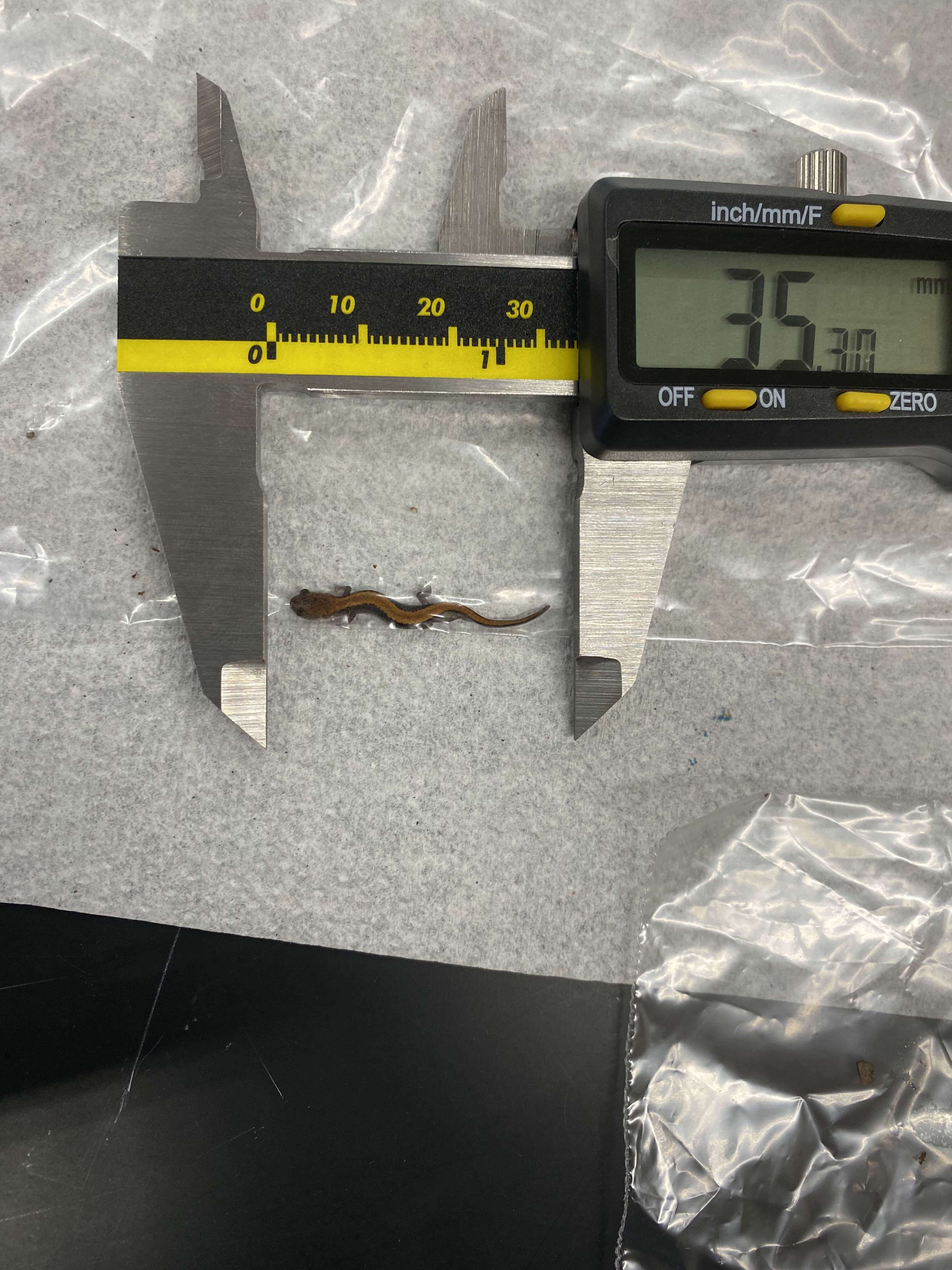

The turtle crew (a gaggle of grad students who mostly work with turtles) and another researcher who works with larger salamanders (Grant) came with us to help with our salamander hunting on Monday. They did all of the capturing, with pretty solid results - 26 salamanders! Including one who was maybe 18 mm snout-to-vent. For reference, the ones we catch are usually adults at 30-45 mm SVL, 60-90 mm total. Obviously, we didn't tag this one, though both L and I got to tag one apiece with the UV elastomer dye. It's a great way to help keep track of our recaptures, since each salamander gets a unique color combination across four sites (the "armpits" of each limb), though the system isn't foolproof - we've found some pretty impressionistic markings on our recaptures. The salamanders are a small target, prone to wiggling at the worst times, and you have to get the dye just barely under their skin or it can potentially travel subcutaneously post-injection and create even more chaos. I was super skittish about it, so I had to take a couple of attempts, but hopefully next time I'll get some more practice. It's a good thing we use serial-coded p-chips as a backup to ensure that we're correct about the identity of our recaptures!

Though Brian was talking about the previous years of this project, and apparently, they weren't always so organized. For the initial set of six - six! - coverboard plots which they were using to survey red-backed salamanders, they didn't use any p-chips, they did all their measurements and tagging in the field, and when they ran out of unique marking codes with the four (technically five, if you count "blank") colors, they just added more to try and fix the problem. In the end, it lead to a lot of messy data - Brian said about 30% of their recaptures were misidentified - and messier marking codes, since it's hard enough to distinguish red and orange UV dye under a salamander's skin without having to wonder if it's actually pink instead. They wound up leaving all six of the original plots alone and switching over to the two plots we have currently, which makes for a much lighter workload (they used to do three plots a day, which sounds exhausting), and they started using the p-chips to help confirm recaptures. It's kind of reasurring to know that even real, grown-up, professional scientists can make those kinds of wonky experimental design choices, and still bounce back from that to make a better design that gathers useful data.

Tuesday was a lecture from Josh on sediment pollution in watersheds, followed by some practice using WEPP to model erosion rates! All of this was prep for the next two days of field work.

On Wednesday, we hiked out to Lewis Falls at Shenandoah National Park, studying the water quality along the way. Before we went on the hike, though, we got to visit the wastewater treatment plant for Big Meadows, which releases their effluent into a natural stream that also feeds into the Falls. We took three samples over the course of the hike: one from the very start of Lewis Spring (or as close as we could get, since the spring is the main water source for the Big Meadows infrastructure, so they have it a bit more controlled), one downstream of the wastewater flow, and one at the Falls where both of the first two streams have joined up. My group was in charge of measuring the alkalinity, which involved doing titrations in the field - not my favorite chemistry skill, but it was a lot less stressful than when I last had to do it in a lab! It was a gorgeous day, so we got some wonderful views from the Falls when we ate lunch. After how foggy our Big Meadows trip in week 4 was, it was nice to actually see everything.

We also stopped by Hawksbill Creek in Luray on the way back to campus to do more water quality testing, as well as macroinvertebrate sampling. Sadly, the flooding from Helene in the past week must have washed most of the critters downstream, because we barely found anything. Those that we were able to find were all good signs, though - mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies. All indicator species that can give a more long-term idea of the stream's quality than snapshot chemical analyses!

Thursday was more field work, starting with a trip to our local watershed at Happy Creek. We found some absolutely enormous crayfish (relatively speaking) and a good variety of macroinverts, which makes sense - the stream was pretty clear, minus some litter from the nearby playground. We also got to practice measuring for discharge rate there, by taking the width, depth, and velocity of a portion of the stream.

Then we were off to Seven Bends State Park (where Jenna and Rachael have their practicum) to do more sampling there. That was definitely the most abundant area for macroinverts! Two hellgrammites, four snails, more mayfly larva than you could ever need, and one stonefly larva that I can only describe as distressingly buff. I didn't get a picture of it, but the photo below gives a pretty good idea of what it looked like - it almost seemed to have muscles! According to Jim, they'll even do "pushups" in low-oxygen conditions, since their gills sit right below their limbs, like feathery, oxygenated armpit hair. Weird, but cool.

Our last stop was further down the North Fork of the Shenandoah, as close to the joining point as you can get by (public, accessible) land. As recently the week before, this area had been under water thanks to the flooding, so it was a treacherous mess of mud along the bank. We barely found any critters (except water mites, which were thriving in the anoxic conditions brought on by all that mud), but it was kind of fun to try and trek through the water without falling over. Thank goodness for waders!

We were in the lab all morning on Friday, working to analyze the nitrogen levels in our water samples. It's pretty easy to measure the nitrate levels in the water, but ammonium can't be measured as accurately in the field, because it's in very high demand by the various organisms, so it's usually only present in extremely small amounts. So, in order to get an accurate sense of how much nitrogen was actually in the water, we needed to use some more precise methods to determine our ammonium levels. That mostly consisted of making a standard curve for absorbance and ammonium concentration by creating dilutions from a known ammonium concentrate, which was a good way to practice micropipetting skills. I even got to use a repeating micropipette for the first time!

In the afternoon, we put together a nitrogen budget for Happy Creek based on our data. The actual process was fairly straightforward, since the basic idea of a nitrogen budget is to help determine the degree to which unmeasured factors are having an impact. We took our known and measured nitrogen inputs (rain, mostly) and outputs (based on the discharge we calculated and the total nitrogen levels), put them into the same units (this was the longest part), and then just compared them. Ideally, an undisturbed watershed system should have significantly more nitrogen inputs than outputs (unless the system is a really well-established old growth forest, and even then, that's pretty rare) because everything in the system is hungry for that ammonium - it's a key limiting nutrient for primary production. After a major disturbance, there should be a pretty big jump in exports, because everything is dying, but then new things will start growing again, and that will balance back out to little/no nitrogen output. So, if there's a system where there's any significant export of nitrogen and it's not actively in crisis, you know that there's significant input factors that you haven't been able to measure; primarily something like fertilizer pollution, or another human-caused input.

This was a pretty field-work heavy week, which was nice in a lot of ways! I really enjoyed getting to spend so much time in the water, even though it's been cooling down outside. Catching all those macroinvertebrates was so much fun, too. Back in the summer, when I was running summer camps at Hidden Pond Nature Center, my favorite activity for the kids was hanging out at the creek with nets and seeing what we could find. It's a really great way to do citizen science and get people to care about their local watersheds.